Microbes

The Ultimate Survivors

Essay

Microbes :The Ultimate Survivors

Nasreen S. Haque

7/28/2023

“There is grandeur in this view of life……...from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

― Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species

Water is a defining characteristic of our planet. Oceans cover more than 70% of earth and it is from here that life evolved. We claim water reservoirs as a primary resource; labor to capture it, build around it and even wage wars to protect it. It enables us to travel to unimaginable places and inspires creativity. We create water-based activities which engages the young and old alike. Re-routing of water for agriculture and enhanced food stocks while building canals for access of big ships allows faster delivery of commodities. Water is indispensable for the continual evolution of life. It is the chemical signals in water that performed the biggest symphony to create life and this primitive "life form" travelled in tiny drops across seas and oceans reaching far away continents to form a galaxy of invisible life from which emerged the diversity of life. How is it that the simplest of creature, that is invisible to the naked human eye, managed to survive and flourish against all odds?

If we were to travel back in time, where would we begin? 4 billion years ago, our planet was not as it appears today. This environment was harsh and unrelenting with levels of Hydrogen and Helium in which no life forms could exist. Earth was essentially a giant ball of molten lava with scorching temperatures and was covered with noxious gas. Even if we were to travel 3.5BYA, - our survival would be impossible due to the lack of oxygen in the earth's atmosphere - though dissolved oxygen may have been present in the oceans. The microbes present were anaerobic and required no oxygen. However, the arrival of the bacterium, Cyanobacteria would change this and bring about the most important event that would ultimately lead to the evolution of aerobic or oxygen loving life forms including humans. Cyanobacteria used their chlorophyll to convert the Sun's energy to CO2 and the byproduct was oxygen; this triggered the rise of aerobic microscopic life which would eventually give rise to multicellularity and all life on earth.

Imagine a time where there were no birds, no flamingos. No animals roamed the wilderness, no trees touched the sky and no insects crawled. In fact, there were no animals or plants, - just single celled organisms like the cyanobacteria and yet, the earth was bursting with life. These microorganisms or microbes thrived on the inorganic bounties of virgin earth. Thus began the conversion of rocks to soil while biogeochemical cycles churned the oceans. Both aerobic and anaerobic organisms colonized vast surfaces and formed symbiotic associations; adaptations and natural selection lead to innovations and partnerships lasting billions of years which has created the diversity of life as we see today.

Microscopic organisms dominate every nook and cranny of the planet, including our bodies. We mostly recognize them as pathogens, but most microbes provide services to the planet without which we would not survive.

We encounter their microscopic patterns as slime on water surfaces, bubbles in wine glasses or cryptograms on city walls. Who are these organisms and why are they important?

Invisible to the naked human eye, these tiny creatures, have elaborate metabolic and genetic capabilities, and perform all necessary functions essential for life on earth. their long evolutionary history, microbes have acquired the tools necessary to survive and innovate as they evolve. They have encountered and formed alliances with multitude of other organisms; some long extinct, others in living symbioses driving ecosystems. There have been major mass extinctions in the past where many species have vanquished. Throughout this, microbes have survived by finding new hosts or adapting to multiple hosts, acquiring, or exchanging genes or simply getting rid of unnecessary genes and thus maintaining diverse ecological niches.

How is it that the simplest of creature, that is invisible to the naked human eye, managed to survive and flourish against all odds?

Niche construction

Microbial evolution has been carved by diverse microbial populations that can thrive in novel conditions. As microorganisms have evolved in symbiotic associations with other organisms, conditions that affect animals and plants also influence microbes. As such, microbes occupy specific niches in their hosts. Microbes that live in the digestive tract of insects and animals or the root nodules of some plants, become a source of essential nutrients to the host while the host provides shelter and other resources. For these microbes, most external physical changes are of little consequence, because they are well shielded by the animals’ homeostatic systems. Most microorganisms, however, live free in nature, especially in the soil and oceans. These must continuously adapt and be resilient under such conditions and remain prepared for adverse condition.

Microbes collectively shape their environment via multiple metabolism pathways that leads to the release of toxins, enzymes, metabolites, phages, as well as biofilm production and detoxification capabilities. All this individually, or collectively, may lead to within-host environmental changes. This niche construction by microbes is both elaborate and adaptive and may contribute collectively to improve resource management within a community. For example, microbes may enrich the nutrient supply by secreting or degradation of essential molecules, produce toxins and build resistance against competitors, or establish themselves in a host and environmental surfaces by building biofilms. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, produces a toxin, pyocyanin that is not only toxic to humans but also kills competitors. The biofilm production by nosocomial pathogen Klebsiella pneumonia enhances its antibiotic resistance. Therefore, understanding the life history of host-pathogen evolution and the consequences of these behaviors on the host environment is a pre-requisite for any planned management of disease or ecosystems.

Diversity, Plasticity and Redundancy

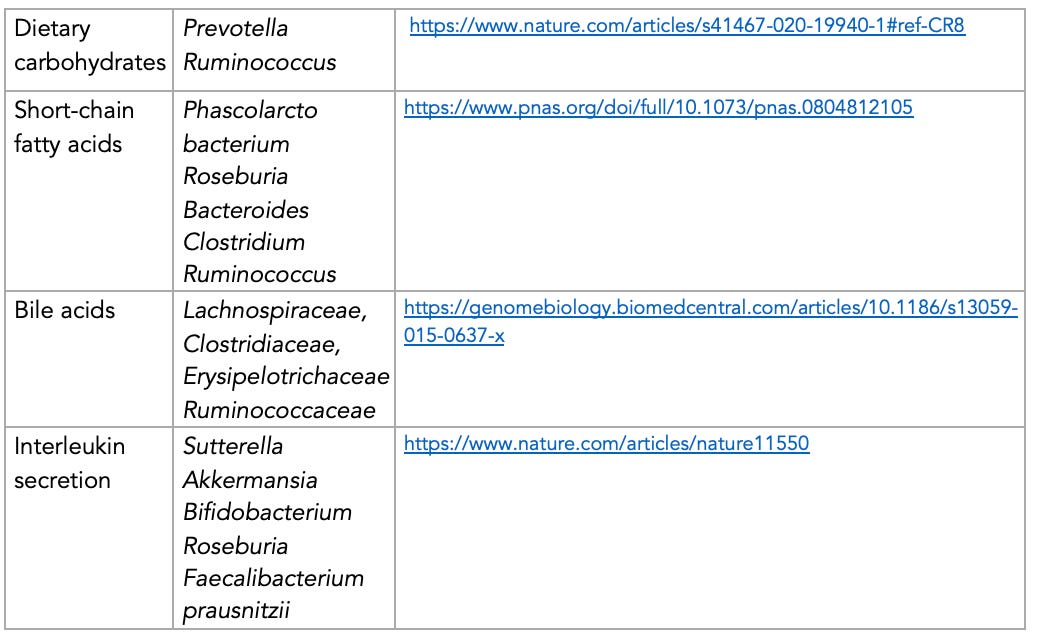

Microbial evolution is based principally on their diversification, phenotype switching (plasticity) and redundant functionality in diverse hosts and environments. Microbial evolution has left remnants of their gene codes equipped with elaborate functional diversity. Genomic sequencing and metagenomic analysis have shown the extent of microbial taxonomical, genetic diversity, and functional variations found in nature as well as in human populations. Moreover, microbes are not only functionally diverse, but they also carry functionally redundant genes; many phylogenetically unrelated taxa have similar genes that attributes to similar functions. Microbial functional redundancy is found across the animal kingdom. While microbial taxa vary within healthy populations, functional compositions of microbes show remarkable conservation across individuals.

In the human microbiome this is accompanied by a significant functional redundancy, implying stability and resilience in response to environmental perturbations. For example, functional redundancy in an ecosystem makes it more resistant to influx of new species with similar functionality to existing species. Having a framework of an organizing principle of the human microbiome could potentially inform other microbiome-based therapies such as fecal transplant or probiotic therapy and provide insights into the relationships between biodiversity and ecosystem function in diverse environments.

A few examples of functional redundancy are presented in the following chart.

Resistance

“Antimicrobial resistance is an urgent global public health threat, killing at least 1.27 million people worldwide and associated with nearly 5 million deaths in 2019. In the U.S., more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year. More than 35,000 people die as a result.”

Antimicrobial resistance is one the world’s most urgent public health problems. Antibiotic resistance is a consequence of ongoing competition for resources among microorganisms in their long evolutionary history. Long before humans started to produce antibiotics to prevent and treat infectious diseases, microorganisms had already evolved multiple mechanisms to tolerate antibiotics produced by competitors. The horizontal transfer of genes has enabled bacteria to mobilize antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) to many other bacterial species enabling the spread of disease. The natural production of secondary metabolites is similar to many of the antibiotics used today in medical treatments. Our indiscriminate use of antibiotics radically changed the preconditions for microbial evolution and is responsible for the unprecedented selection pressures for resistance that we face today. This has particularly affected the rise of resistance in the microbial flora of humans and domestic animals, and even fisheries, as this industry relies on environments which are heavily polluted with antibiotics.

Symbiotic Discordance

When microbes that provide essential services to the host leave under predictable and/or unpredictable circumstances (e.g., antibiotics), other microbes may replace them; bringing redundant or unwelcome functionalities, which are not particularly sought by the host. This perturbs the ecological balance, allowing unwelcome organisms to invade and disrupt symbiotic associations and life-histories, ensuing an on-going arms race. Alternatively, this may enable the evolution of existing genes leading to the acquisition of novel phenotypes which will eventually determine how a situation may be resolved. A drastic shift in equilibrium leads to Symbiotic Discordance (SD) between the host and other symbiotic species present in that niche, where losses can no longer be sustained and rebuilt. In this new anoxic environment unsuitable for the host, conditions now favor cost effective survival of pathogens; consequently, the host immune system is on high alert and a runaway inflammatory response sets into action which may harm the host itself. The host - microbe can no longer function as it formed in stabilized selection. The current rise in chronic inflammatory disorders globally, - a serious concern for human health- is a manifestation of such host-microbe interactions.

Recent studies have shown a direct link between the gut microbiome and the brain. As such, the gut microbiota is being intensely studied, as it is offering novel insights into human and animal malignancies. Microbial strategies have evolved for host selection, colonization, defense, replication, and speciation to increase their own survival. In this process, microbes have learnt to control host behavior. Reciprocally, host response to microbial infections has also evolved and this arms race continues. It is now evident that parasites alter more than one dimension in their host phenotype to increase their own fitness at the expense of that of their hosts. Microbes control host cognition and behavior such as sleep patterns, mood swings (depression, bipolar disorder, or manic depressive), physical fitness, anger, frustration, and reproduction. These multidimensional phenotypic alterations have been observed in many host–parasite associations across species. This is so pervasive it can be termed as the extended phenotype of the microorganism.

We must acknowledge our place as newcomers in this planet. Our evolutionary history is much too recent to have acquired the entire arsenal to compete with microbial evolutionary advantages. We have altered the ecological balance of our planet that threatens the biodiversity of life. Loss of biodiversity has a domino effect on all other aspects by decreasing functionality,- loss of habitat, reduced survival in novel environments, limited access to resources. To make matters worse, when options are limited microbes are pushed towards pathogenicity leading to dysbiosis or loss (Missing Microbes by Martin Blazer) from host and/or SD. Antibiotic resistance microbes are crossing species boundaries to invade new environments. Insights into the dynamics of bacterial re-distribution of biochemical byproducts into its environment and niche construction strategies have the potential to improve human health and disease and to manage this global health challenge.

Source:

1. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing by Qin, J. et al. in Nature, 2010.https://www.nature.com/articles/nature08821

2. Diversity, stability, and resilience of the human gut microbiota by Lozupone, C. A., et al. Nature, 2012. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11550

3. Deciphering functional redundancy in the human microbiome by Liang Tian et. al. in Nat Communications, 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19940-e

4. The role of natural environments in the evolution of resistance traits in pathogenic bacteria by Martinez, J. L. in Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 2009. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2009.0320

5. The origin of niches and species in the bacterial world by Fernando Baquero in Frontiers of Microbiology, 2021. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.657986/full

.